Posts

One noted behavioral scientist, Frederick Herzberg, in his 2-Factor Motivation Theory (1959) made a distinction between job dissatisfaction and satisfaction.

He argues that Satisfaction for an employee comes from truly motivating factors such as interesting and challenging work, utilization of one’s capabilities, opportunity to do something meaningful, recognition of achievements, and responsibility for one’s own work.

Dissatisfaction occurs when the following factors are not present on the job: good pay, adequate holidays, long enough vacations, paid insurance and pensions, Good working conditions, and congenial people to work with.

Herzberg’s 2-Factor Motivation Theory

Herzberg bases these definitions on what is now known as the 2-Factor or the Motivation-Hygiene Theory. He says that every human being has two motivational tracks: (1) a low-level aspect, which is animal in nature and bent only on surviving, and (2) a higher-level aspect, uniquely human and directed toward adjusting to oneself.

Herzberg labels the first set of motivations hygiene or maintenance, factors. We need to satisfy them, he reasons, to keep alive people try to avoid pain and unpleasantness in life; they do the same on the job.

The satisfaction of these needs provides only hygiene for people. These factors physically maintain the status quo, but they do not motivate. If they are not present in the workplace, an employee will be dissatisfied and we look for a job elsewhere that provides these factors. But the employee will not work harder just because these factors are given to him or her. Said another way, A general pay increase may keep employees from quitting but it will rarely motivate an employee to work harder.

So how can supervisors provide the kind of satisfaction that motivates team members?

Herzberg feels that those job factors that provide genuine and positive motivation should be called satisfiers (motivators).

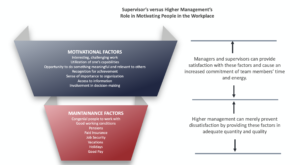

Without splitting hairs, we can see that generally, the company must provide the factors that prevent dissatisfaction. The supervisor tends to provide the factors that satisfy. Few supervisors can establish the basic periods for the organization.

Yet, almost all supervisors can motivate. For example, the supervisor can provide an employee with a specific, challenging goal: “Not many people can pack more than 200 cartons an hour. If you can pack 220 today, you will be a great asset to this Department.”

Similarly, a supervisor can let an employee know that the work he or she is doing is appreciated: “My manager asked me today who it was that prepared these urgent reports. I was pleased to tell her that you did!”

A leader can also help to make work more interesting by making suggestions, such as, “Why don’t we take 15 minutes later this afternoon to see whether we can find a way to break the monotony in your job?”

Finally, leaders can always extend responsibility by saying to an employee, “Beginning today you will make the decision as to whether off-grade products should be reworked or thrown away? If you make an occasional mistake, don’t worry about it in that area your judgment is every bit as good as mine.”

By looking at Herzberg’s theory of motivating people, leaders will be able to know how to effectively connect, build relationships and encourage their people to give their best in the workplace.

As we realize that maintenance factors such as benefits, security, working conditions and a fairly good pay can only do so much, we can maximize motivation and ultimately, performance, by having our team members explore their uniquely human needs to achieve greater through involvement, appreciation, and sense of importance in the workplace.

REFERENCES Herzberg, Frederick; Mausner, Bernard; Snyderman, Barbara B. (1959). The Motivation to Work (2nd ed.). New York: John Wiley. Herzberg, Frederick (January–February 1964). "The Motivation-Hygiene Concept and Problems of Manpower". Personnel Administration (27): 3–7. Hines, George H. (December 1973). "Cross-cultural differences in two-factor motivation theory". Journal of Applied Psychology.

Most of us, including our team members and peers, seek satisfaction from life in relation to what Abraham Maslow called the “five basic needs.” And we seek a good part of this satisfaction at our work. Maslow outlined these basic needs, and we’ll try to explain these needs as conceived from his hierarchy, with the most compelling ones coming first and the more sophisticated later.

We Need to Be Alive and to Stay Alive

We Need to Be Alive and to Stay Alive

We need to breathe, eat, sleep, reproduce, see, hear, and feel. But in today’s world, these needs rarely dominate us. Real hunger – for example – is rare in most societies. All in all, our first level needs are satisfied. Only an occasional experience – a couple of days without sleep, a day on a diet without carbs or sugar, a frantic 30 seconds underwater – reminds us that these basic needs are still within us.

We Need To Feel Safe

We like to feel that we are safe from accident or pain; from competitors or criminals, from an uncertain future or a changing present. Not one of us ever feels completely safe. Yet most of us feel reasonably safe. After all, we have laws, police, insurance, social security, employment contracts, etc. to protect us.

We Need to be Social

From the beginning of time, we have lived together in tribes and family groups. Today, these group ties are stronger than ever. We marry, join clubs and even pray in groups. The social need varies widely from person to person – just as other needs do. Few of us want to be hermits. Not everyone, of course, is capable of frank and deep relationships – even with a wife or husband and close friends. But, to a greater or lesser degree, this social need operates in all of us.

We Need to Feel Worthy and Respected

When we talk about our self-respect or our dignity, this is the need we are expressing. When a person is not completely adjusted to life, this need may show itself as undue pride in achievements, self-importance, boastfulness – a bloated ego.

But so many of our other needs are so easily satisfied in the modern world that this need often becomes one of the most demanding. Look what we go through to satisfy the need to think well of ourselves – and have others do likewise. When a wife insists her husband wears a jacket to a party, she’s expressing this need. When we buy a new car even though the old one is in good shape,l we’re giving way to our desire to show ourselves off, paired with the need to validate our achievements and status.

We even modify our personalities to get the esteem of others. No doubt you’ve put on your company manners when you represent the organization. It’s natural, we say, to act more refined in public than at home – or to cover up our less acceptable traits.

We Need to Do the Work We Like

This is why many people who don’t like their jobs turn to hobbies for expression, and why so many people get wrapped up in their work. We all know men and women who the hard burden of laboring work, or workers in a manufacturing plant who hurry from work to run their own lathes or bored terminal operators who stay up late in their own homes doing lifelong hobbies.

This need rarely is the be-all and end-all of our lives. But there are very few of us who are not influenced by it.

In the United States in the 1960s and early 70s, many young people dropped out of society to set out to do their own thing. This was largely an expression of the desire to fulfill oneself – the need for Self-Actualization.

So which of these needs is the most powerful? We say, the ones that have not yet been satisfied.

Maslow’s greatest insight was the realization that once a need is satisfied, it will no longer motivate a person to greater effort. If a person has what is required in the way of job security, for example, offering more of it – such as guaranteeing employment for the next five years – will normally not cause a person to work harder.

The leader who wishes to see greater effort generated will have to move to an unsatisfied need, such as the desire to be with the other people on the job, if this employee is to be expected to work harder as a result.

***

Having explored Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs once again emphasizes the importance of how leaders should be vastly aware of their people’s motivation. With the undying question on motivating our team members, leaders can utilize this awareness and embrace such needs – both of their own and of their people.

Why don’t employees act the way you wish they would? The answer will take a long time. But if what you are really asking is, “why do people act in such unpredictable ways?” the answer is simple: People do as they must. Their actions, which may look irrational to someone who doesn’t understand them, are in reality very logical.

If you could peer into people’s backgrounds and into their emotional makeup, you’d be able to predict with startling accuracy how one person would react to criticism or how another person would act when told to change over to the second shift.

Like a dog who’s been scratched by a cat steers clear away from all cats. Employees who have learned from a manager that the only time they are treated as human beings is when the workload is going to be increased will be on the defensive or cautious when a new boss tries to be friendly. To the new leader, such team members’ actions may look absurd, but for them, it’s the only logical thing to do.

People behave differently because of their uniquely different backgrounds and personalities.

So as it goes, each person is the product of parents, home, education, culture, social life, and work experiences. Consequently, when leaders deal with their team members, they are dealing with people who have brought all their previous experiences to the job.

Thus, each person is different. Each is a distinct individual. In detail, one’s reactions will be different from anyone else’s. But to understand human relations, we must first know why people do things before you can predict what they will do.

Say for example that Marvin dislikes his job because it requires a certain level of concentration, you can make a considerable guess that you will find more resistance from him when you offer another job that requires more complex tasks. Or if Jane, who is known to be a great people-person, a leader can predict that it will hard for her to take on roles in an isolated area.

The important tool in dealing with people is the recognition that although what they do is likely to differ, the underlying reasons for their doing anything are very similar. These reasons are called motives or needs.

So what determines personality? Well, just about anything. An individual’s personality cannot be pigeonholed as pleasant or outgoing or friendly or ill-tempered or suspicious or defensive. An individual’s personality is the total of what the person is today.

Each person’s personality is uniquely different from anyone else’s. It results from his/her own nature and nurture like schooling or lack of it, neighbors, peers, work and play experiences, parents’ influences, religion, etc.

From these influences, people learn to shape their individuality in a way that enables them to cope with life’s encounters, with work, with living together, with age, with success and failure. As a result, personality is the total expression of the unique way in which each individual deals with life.

Having laid down these facts about individualities and varying personalities in the workplace, leaders need to learn how to effectively delve deeper into each of their team member’s motives and wants. They may vary depending on each’s personalities and preferences, but as soon as the leader identifies and embraces these aspects and aligns motivations with his/her people, motivation follows.

References: Giuliani, R. W., & Kurson, K. (2007). Leadership. London: Sphere. Littauer, F., & Sweet, R. (2011). Personality plus at work: how to work successfully with anyone. Grand Rapids, MI: Revell. Maslow, A. H., Stephens, D. C., & Heil, G. (1998). Maslow on management. New York: Wiley.